Wedding Traditions among the Agĩkũyũ People of Kenya

by Alex Bliss

About Alex

The Agĩkũyũ people speak the Bantu language and form the largest ethnic group in Kenya. They are also known as Nyumba ya Mumbi which means The House of the Potter. The Agĩkũyũ inhabit five counties almost exclusively, namely: Kiambu, Nyeri, Nyandarua, Murang’a, and Kirinyaga. They arrived in Kenya during the 1200-1600 AD Bantu migrations.

The Agĩkũyũ people speak the Bantu language and form the largest ethnic group in Kenya. They are also known as Nyumba ya Mumbi which means The House of the Potter. The Agĩkũyũ inhabit five counties almost exclusively, namely: Kiambu, Nyeri, Nyandarua, Murang’a, and Kirinyaga. They arrived in Kenya during the 1200-1600 AD Bantu migrations.

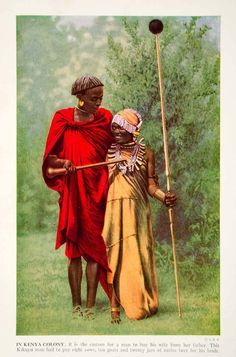

Traditional Wedding – 1938

Traditional weddings among the Agĩkũyũ are not popular today but there are still people who hold fast to them. An abridged form of the indigenous customs is what we see today. People will avoid the protracted ceremonies and the traditional wedding adornments but still have some sense of attachment to their roots.

If a young man identified his prospective wife, he prepared mũratina brew for his father and his friends prior to announcing his marriage intention. It was during the entertainment he told them about his readiness to have a wife. When the news had been passed, the young man’s family prepared him and a group of young men to go to the bride’s home to know where she lived. This was followed up with yet another visit by a group of elders. These visits are called kũmenya mũciĩ , to know the bride’s home, in the original Kikuyu dialect.

If it happens that the girl visits the groom’s home first, she is subject to implicit scrutiny by her mother-in-law to be. She is tactfully vetted to ascertain her suitability as a wife and a new daughter to the family. The man of the house will not talk or ask the girl any questions. It is not for him to do that and he cannot meddle with women’s affairs. If the young man’s mother was not pleased with the girl, she tried to ask her son to change her mind but not with much success. If the two lovers learned that their parents were opposed to their marriage, they eloped to some faraway place to live happily ever after.

If it happens that the girl visits the groom’s home first, she is subject to implicit scrutiny by her mother-in-law to be. She is tactfully vetted to ascertain her suitability as a wife and a new daughter to the family. The man of the house will not talk or ask the girl any questions. It is not for him to do that and he cannot meddle with women’s affairs. If the young man’s mother was not pleased with the girl, she tried to ask her son to change her mind but not with much success. If the two lovers learned that their parents were opposed to their marriage, they eloped to some faraway place to live happily ever after.

Proposal to the bride’s father

When the young man is ready, he looks for a representative to accompany him to the girls home. Through his representative he tells the girl’s father, “My father wants to make a lasting friendship with you.

When the young man is ready, he looks for a representative to accompany him to the girls home. Through his representative he tells the girl’s father, “My father wants to make a lasting friendship with you.

The young man is interrogated. He specifies which girl interests him after which the boy invites him to his home to fare in njohi ya njũrio, beer of the asking. He would never refuse such an offer unless he didn’t want to give his daughter in marriage. He was accompanied by his wife or wives, his brothers and their wives and some elders. This ceremony was an ideal setting to discuss the proposal and to accept it formally.

Expressing intentions

At this stage, the groom in company of a group of young men visits the bride’s father to state his intentions. It is done in such a way that it will soften the heart of the father-in-law to be. The groom does not go empty handed; he must have a token for his soon to be in-laws. It does not have to be farm produce or sheep or goats today. A good shopping can do. It is a serious affair if done the old way but manageable as well. This is called kũhanda ithĩgĩ, planting of twigs, to mean that intentions have already been stated and that no other young man can come after the same girl thereafter. Usually, twig planting goes with a handsome gift to the bride’s family which, however alluring, is not part of the actual dowry payment. The amount of money to give is for the groom’s family to decide, they can give little or much. However, if the hospitality they are given “shames” the token they are to give out, they are within their customary rights to ask to be allowed gũthiĩ ndundu, to meet in private, in order to raise a good amount of money or else they’ll appear mean. This visit prepares both sides for dowry negotiations.

At this stage, the groom in company of a group of young men visits the bride’s father to state his intentions. It is done in such a way that it will soften the heart of the father-in-law to be. The groom does not go empty handed; he must have a token for his soon to be in-laws. It does not have to be farm produce or sheep or goats today. A good shopping can do. It is a serious affair if done the old way but manageable as well. This is called kũhanda ithĩgĩ, planting of twigs, to mean that intentions have already been stated and that no other young man can come after the same girl thereafter. Usually, twig planting goes with a handsome gift to the bride’s family which, however alluring, is not part of the actual dowry payment. The amount of money to give is for the groom’s family to decide, they can give little or much. However, if the hospitality they are given “shames” the token they are to give out, they are within their customary rights to ask to be allowed gũthiĩ ndundu, to meet in private, in order to raise a good amount of money or else they’ll appear mean. This visit prepares both sides for dowry negotiations.

Dowry negotiations and payment

Dowry negotiations and payment

This is called rũracio. When the groom and his entourage arrive at the bride’s home, they find the gate closed. That is a message that they must sing their way in, so a lot of singing by women of both houses at the entrance before the groom’s parents makes their way into the home takes place. Each group of women sing songs so that it looks like a vocal challenge, in the end, they join in united singing, symbolic of two different families that start differently but end up together with a shared and a united purpose. This is important step to signal new familial ties that will last for a lifetime. As this happens, the bride is hidden in some secret place and only emerges when she is called upon by the emcee. The master of ceremony takes charge. He might say, “We got a flower in this home, it is very beautiful, that’s why we have come back.” People give tokens, money, and drinks are served. Women on the girl’s side are given lessos. The groom’s envoy is asked to produce a towel to wipe the sodas, plus gikunũro, an opener, all in form of cash.

At the same time, the master of ceremony asks the bride if her father should accept a drink as a way of asking for her consent to be married. If she consents, there is ngemi, jubilation—alililililili. They do it three times; customs have it that that is what befits a girl. As a sign of appreciation, gũcokia guoko, the crates of soda must be given back to the bride.

To set stage for the most important part of the day, food is served. Mũkimo is usually a favorite to many. It is prepared from thafai (stinging nettle), potatoes, beans. Pumpkins can be used in place of potatoes depending on people’s tastes and preferences. The end product is a soft thick mixture with dough-like consistency that is served with some gravy and chicken or beef. There must be alternatives, chapatti, njahĩ (black beans), mũkano (bananas), and roast meat. When everyone has eaten to their fill, introductions are done and negotiations ensue.

By this time both parties are well-braced for the task that waits. The parents of both the bride and the groom do not speak to each other directly on a day like this. They have spokespersons. The groom is accompanied by a young man who is his friend to represent him except when he is required to state which girl tickles his fancy. You expect heavy use of euphemistic language, use of proverbs and idioms and goodness knows what else; therefore, these representatives must have a certain level or language wizardry for the day to be a success.

If the groom’s entourage is ready to pay the dowry, athuuri, the men on the bride’s side, proceed to give their catalog of the required items and then wait for their counterparts to either agree or dispute. Atumia, the women, also proceed to give their requirements as required by the bride’s family.

The dowry could comprise of:

- Goima: A fattened ram

- Thenge (He-goat)

- Cows

- Mori (Heifer)

- Njohi ya ũũki: This is beer made from honey for elders as a sign of respect

It is worth noting that the demands made by the bride’s family can be challenged. That’s why the groom’s family has to choose their representative wisely to be able to secure a fair deal. It is customary to stretch the arguments for long with the express purpose of wanting to tire one side and to get them to give in. If both sides reach an impasse, the groom’s party will withdraw for a bit, go outside to see what they can do. Usually, they return with the same stand of a subsidized payment. They can; however, decide to make the deal fairer for the bride’s party and add to their payment.

In the event of the groom not completing his dowry payment, he is asked to keep it in mind lest he brings his family embarrassment.

The showing of the nesting place

The bride and her family go to the groom’s homestead so she can be shown her new home, her new kitchen and how her mother-in-law has set it up. This is called Kũonio itara, to be shown a nesting place. Itara is a nest. Itara also denotes a place where firewood is stored but the contextual meaning here is the bride’s new homestead. It is her nesting place; her bridal abode. This is a relaxed event with no formalities or stilted conversations. It is an opportunity for both families to know each other better and to develop stronger bonds.

The wedding

The Agĩkũyũ customary wedding is called ngurario. The action itself is Kũguraria or gũtinia kĩande , Kũguraria means to injure or to maim. Gũtinia kĩande means to cut the shoulder. This ceremony involves cutting one of the front limbs of a fattened ram. It is presided over by a married couple at the home of the bride. Prior to this ceremony, the groom visits bride’s father to enquire on what to give. If he had not completed his dowry payment, rũracio negotiations are centered on completing that payment.

The Agĩkũyũ customary wedding is called ngurario. The action itself is Kũguraria or gũtinia kĩande , Kũguraria means to injure or to maim. Gũtinia kĩande means to cut the shoulder. This ceremony involves cutting one of the front limbs of a fattened ram. It is presided over by a married couple at the home of the bride. Prior to this ceremony, the groom visits bride’s father to enquire on what to give. If he had not completed his dowry payment, rũracio negotiations are centered on completing that payment.

The women accompanying the groom to the bride’s home carry a lot of gifts including flour, sugar, cereals and bunch of bananas. They sing a lot at the gate, still carrying their gifts. It is an offense to put them on the ground so the women must by all means remain strong the whole while. The songs are a polite request that the gate be opened for the groom’s entourage. On the other side of the gate, the women in the bride’s home will also sing in response to the plea so that it becomes a sing-song exchange with its culmination being the gate being opened.

Both parties share a meal together and introductions are made, just like in the day of rũracio. The bride is hidden among a group of 10 to 15 women; all dressed in lessos and veiled completely from head to toe and the groom is required to pick his bride out. He cannot cheat! But *I tend to think lovers could privately agree on something that could make the test simpler, say some subtle body signals. If he fails the test, he gets penalized.

Once the bride has been identified, both the bride and the groom change into the wedding adornments. The shoulder to be cut is ready on the traditional table for everyone to see. The emcee asks the groom to cut the limb assisted by his wife. When that is done, the master of ceremony tells the groom that albeit the wife gives birth to a child, the responsibility of taking care of it lies squarely on him as the man of the home.

Eating the ears

This tradition involves eating goat’s ears. The groom gives his bride goat’s ears to eat. When she is done, she in turn gives her husband, who also eats them. This serves to remind them that they should always listen to each other; that the companionship they have entered into requires both of them to pay attention to each other. Other women present also eat goat’s ears to remind themselves to listen to their husbands; however, they have to be about the same age as the bride. Older women don’t partake in this.

Eating porridge

The bride is instructed to do several things before feeding his groom with some porridge. She combs his hair, cuts his nails, and polishes his shoes. A group of around five men on both sides are also called to sit in front so their wives can also feed them with porridge. The porridge is served in a calabash. The groom will pretend he doesn’t want it and will turn his head to face the opposite direction; all he wants is to be soothed. Eventually, he accepts and the bride is happy. The other men follow and their wives serve them with the same porridge.

After eating porridge, some representatives from the groom’s side withdraw to meet with their counterparts on the bride’s side to pay some more dowry albeit in the Agĩkũyũ traditions, it is said that, “ũthoni ndũthiraga,” dowry is never finished. This is what discounts the notion of “selling the bride” in this community. Thus, the man, if he can, continues to help his in-laws as long as they live.

Marriage certification

After Kũguraria, the master of ceremony calls upon the newlyweds in front of the gathering and announces that both have rightfully been joined in a traditional Agĩkũyũ wedding, reads out the certificate number and proclaims their union legal. They are then awarded with the certificate.